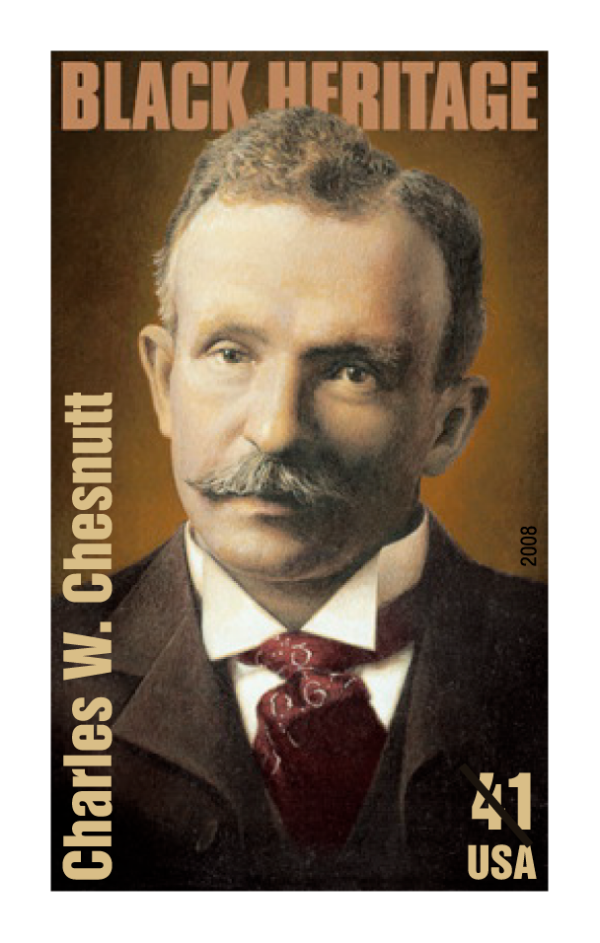

About This Stamp

With the 31st stamp in its Black Heritage series, the U.S. Postal Service honors Charles W. Chesnutt, a pioneering writer whose work addressed a broad range of African-American experience during the post-Civil War period known as the Reconstruction era. Chesnutt made an important breakthrough when his short story “The Goophered Grapevine” appeared in the August 1887 issue of Atlantic Monthly. He was proud to be published in such a prestigious publication, and was one of few African-American writers to have done so at that time.

Written partly in dialect, “The Goophered Grapevine” tells two stories: The first, narrated by a white northerner who becomes a gentleman farmer in North Carolina, frames a longer narrative by “Uncle” Julius McAdoo, an ex-slave who entertains and subtly instructs his listeners with tales of voodoo. “The Goophered Grapevine” and other stories using the identical framing device were collected in The Conjure Woman, published in 1899. A faint whiff of authorial ridicule clings to Chesnutt’s white narrator, who is stolid, condescending, and perhaps a bit obtuse—but far from wrong when, commenting on Julius’s tales, he remarks, “Some of these stories are quaintly humorous; others wildly extravagant … while others … disclose many a tragic incident of the darker side of slavery.”

Indeed, a striking aspect of the stories in The Conjure Woman is the way they are poised between comedy and tragedy. Chesnutt was proud to receive a positive review from the eminent writer and critic William Dean Howells, who wrote: “The stories of The Conjure Woman have a wild, indigenous poetry…. Character, the most precious thing in fiction, is faithfully portrayed.” Today, Chesnutt’s writings are admired for their probing psychological exploration and for their progressive thinking on questions of race.

Chesnutt published a second collection, The Wife of His Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line, later in 1899. His first published novel, The House Behind the Cedars (1900), detailed the frustrated efforts of an accomplished but naive young woman to pass for white. Another novel, The Marrow of Tradition (1901), inspired by a race riot that took place in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898, presents a panoramic survey of race relations in the fictional town of Wellington. Describing this work at the time it was composed, Chesnutt wrote: “The book is not a study in pessimism, for it is the writer’s belief that the forces of progress will in the end prevail, and that in time a remedy may be found for every social ill.”

Chesnutt himself was of mixed racial descent, which gave him insight into a variety of viewpoints along America’s color line. Near the end of his life he wrote: “As a matter of fact, substantially all of my writings, with the exception of The Conjure Woman, have dealt with the problems of people of mixed blood, which … are in some instances and in some respects much more complex and difficult of treatment, in fiction as in life.”

In The Colonel’s Dream (1905), the last of his novels to be published during his lifetime, Chesnutt attacked the failures of Reconstruction, which, he argued, threatened to consign many black people to conditions as bad as they had been during the years of slavery. His other writings include essays, poems, a biography of Frederick Douglass, and several unpublished works. Chesnutt was politically active and frequently spoke out against racial discrimination.

In 1928, Chesnutt received the Spingarn Medal, awarded by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for “distinguished service” to the aspirations of African Americans. In giving him the award, the NAACP cited Chesnutt’s “pioneer work as a literary artist depicting the life and struggles of Americans of Negro descent.”

Chesnutt was born on June 20, 1858, in Cleveland, Ohio. His father served in the Union Army during the Civil War and subsequently brought his wife and children to Fayetteville, North Carolina, which became the major setting of Chesnutt’s fiction. He received a fairly solid general education, but taught himself shorthand, ancient languages, and other subjects. As a very young man, he taught school briefly and then served as principal of a normal school for African Americans in Fayetteville.

Subsequently, Chesnutt settled in his birthplace, Cleveland. After becoming established there, he sent for his wife, Susan, whom he had married in 1878, and his children, who had remained in Fayetteville. He got work in a law office and studied law, passing the Ohio bar examination in 1887; he became a wealthy man operating a court stenographic service.

Chesnutt died at his home in Cleveland on November 15, 1932. In recent years, his work has attracted growing interest. Today Chesnutt is recognized as a major innovator and singular voice among turn-of-the-century literary realists who probed the color line in American life.

Stamp Art Director, Stamp Designer

Howard E. Paine

A member of the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee before being named an art director in 1981, Howard E. Paine supervised the design of more than 400 U.S. postage stamps. After three decades as an art director for the U.S. Postal Service, he retired in 2011.

For more than 30 years Paine was an art director for the National Geographic Society, where he redesigned National Geographic magazine, developed the children’s magazine, National Geographic World, and designed Explorers Hall. A popular lecturer, he has spoken at Yale University and New York University, among others, and presented programs for the National Park Service and the Smithsonian Institution. A judge for numerous art shows and design competitions, Paine also taught magazine design at The George Washington University.

Paine had been a stamp collector since childhood. In 2000, he designed the catalog for Pushing The Envelope: The Art of the Postage Stamp, an exhibit of original stamp art at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Howard Paine died on September 13, 2014.