Ansel Adams

Can postage stamps convey a mood? Consider the magic and whimsy of the Harry Potter collection, the dignity of John Lewis, and the colorful energy of Art of the Skateboard. Each invites you into a completely different world in miniature.

Art director Derry Noyes considered that question as she contemplated the breathtaking black-and-white photography of Ansel Adams. How to capture the serenity and majesty of his environmental portraits?

“I have always been in awe of Ansel Adams,” she says, wondering “how in the world he created so many beautiful images.”

Adams himself spoke of the delicate dance between preparation and chance in making a picture. “There’s a wonderful quote of his that I have on an old print: ‘Sometimes I think I do get to places just when God’s ready to have somebody click the shutter,’* shares Noyes. "And there’s a picture of him on top of his truck with his camera, just standing there in front of these mountains,” ever ready for what might appear beyond the lens.

Limiting the options

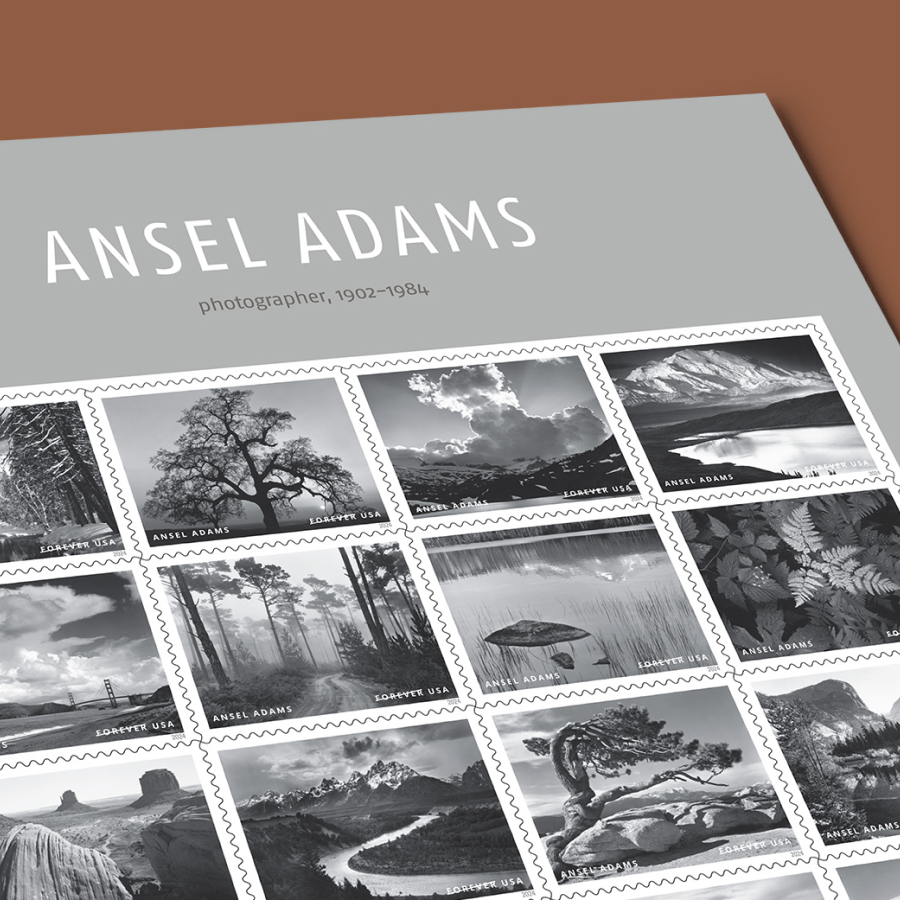

At the start of the project, Noyes put some constraints in place: using only horizontals, for example, to better capture the sense of landscape and to bring continuity. “It’s calming to have them all the same,” she says. “If you’re wanting to liven things up, maybe you mess around with vertical and horizontal. What’s serene about this is the common denominator. Then it’s the details inside the photographs that you focus on.”

Another constraint involved simply the number of photos she could use. Adams (1902–1984) had published more than 1,500 images in his career. Noyes would, in the end, use only 16 — a combination of her own choices and those of his estate.

“Working solely with black-and-white photography was a pure joy,” she says. “We are flooded with so much color that we forget how powerful and soothing it is to work in black and white.”

Soothing, along with serene and classic, became words that defined how Noyes wanted to arrange the stamps — creating a rhythm from stamp to stamp.

“If the road is going off to the right [in one photo],” Noyes explains, “maybe you want the river to go around to the left [in another]. It’s totally subjective — a matter of how does it feel balance-wise?”

As the collection of choices shifted and changed, Noyes would physically cut out images and manipulate them manually. Then she’d replicate the same order on her computer, print out the arrangement, and determine if the balance felt right.

“You wouldn’t want to have the three mountains all together,” she says, as one example. Instead, she separated them, mixing in a closeup of a fern, some tall trees, clouds, and more. “The variety from one to the next works.”

Then she carefully chose a simple typeface for the text on the stamp so as to not distract from each image. ”Sometimes you want the type to be bold, to be a presence that smacks you in the face. Not in this case.”

Learning to think small

Noyes actually found it amazing that Adams’s majestic images worked so well at stamp size. Although she believes that every topic can be conveyed on a stamp, the choosing of images is a complicated dance. “It’s an adjustment, thinking this small — learning what to leave out,” she explains. “You wouldn’t choose something that’s too intricate, for example. The stamps that are strongest have good contrast, white space, and are not too monochromatic, not too busy.”

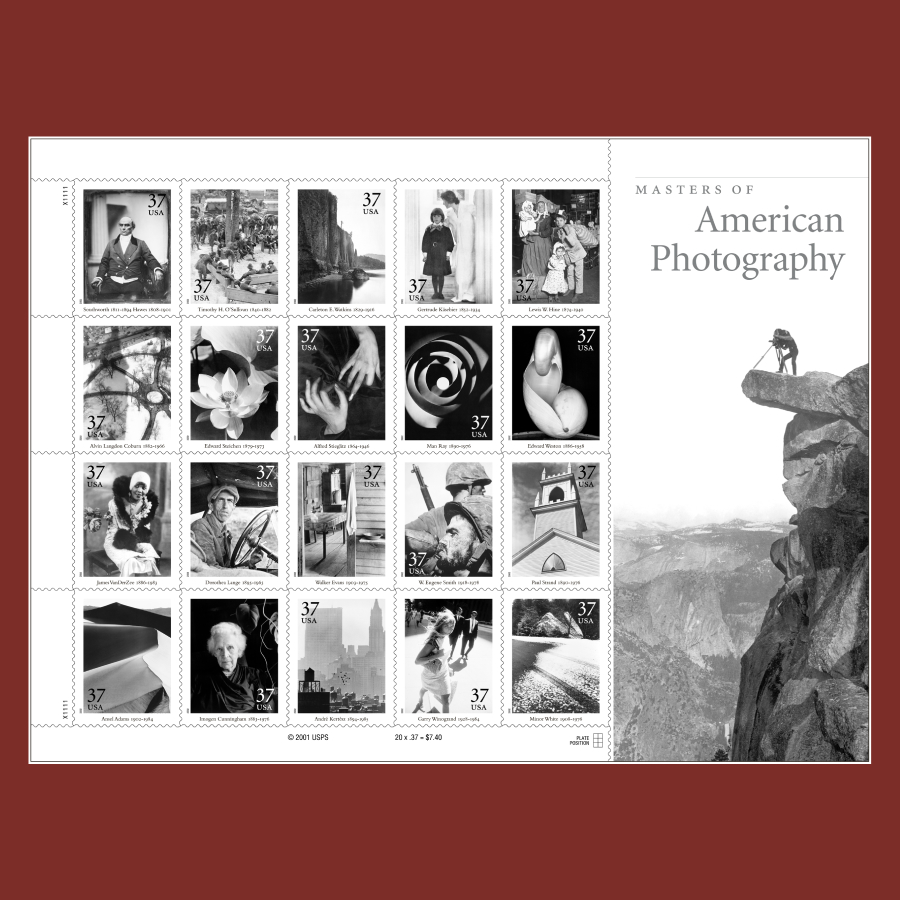

Noyes also featured an Adams image when she worked on the Masters of American Photography issuance in 2002 — featuring 20 different photographers. “I had to work hard to find those that hold up at stamp size. But all of Ansel Adams’s do. It’s the tonal quality, the different shades of gray,” she explains, noting how Adams composed each of his images with deep knowledge and great care. Before clicking the shutter, he visualized the final print he wanted to achieve, and then brought it forth into fruition.

Safeguarding the environment

Adams’s own dive into photography occurred in 1916 after his parents gave him a Kodak Brownie No. 1 box camera. His first photos featured the Yosemite Valley, taken while on a family trip. Future trips hiking in the California mountains developed his love both of this new skill and of the environment.

Sometimes I think I do get to places just when God’s ready to have somebody click the shutter.*

Adams would go on to change how people viewed photography — not merely as a way to record something but as art. He would visualize how a subject felt to him emotionally, rather than how it looked. Fellow artists regard Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, 1927 as his first masterpiece.

Over his seven-decade career, Adams also advocated for environmental policies that would safeguard the wild places he had worked so hard to capture on film.

Would he ever have imagined how the awe he inspired in his art might be shared in miniature with the world?