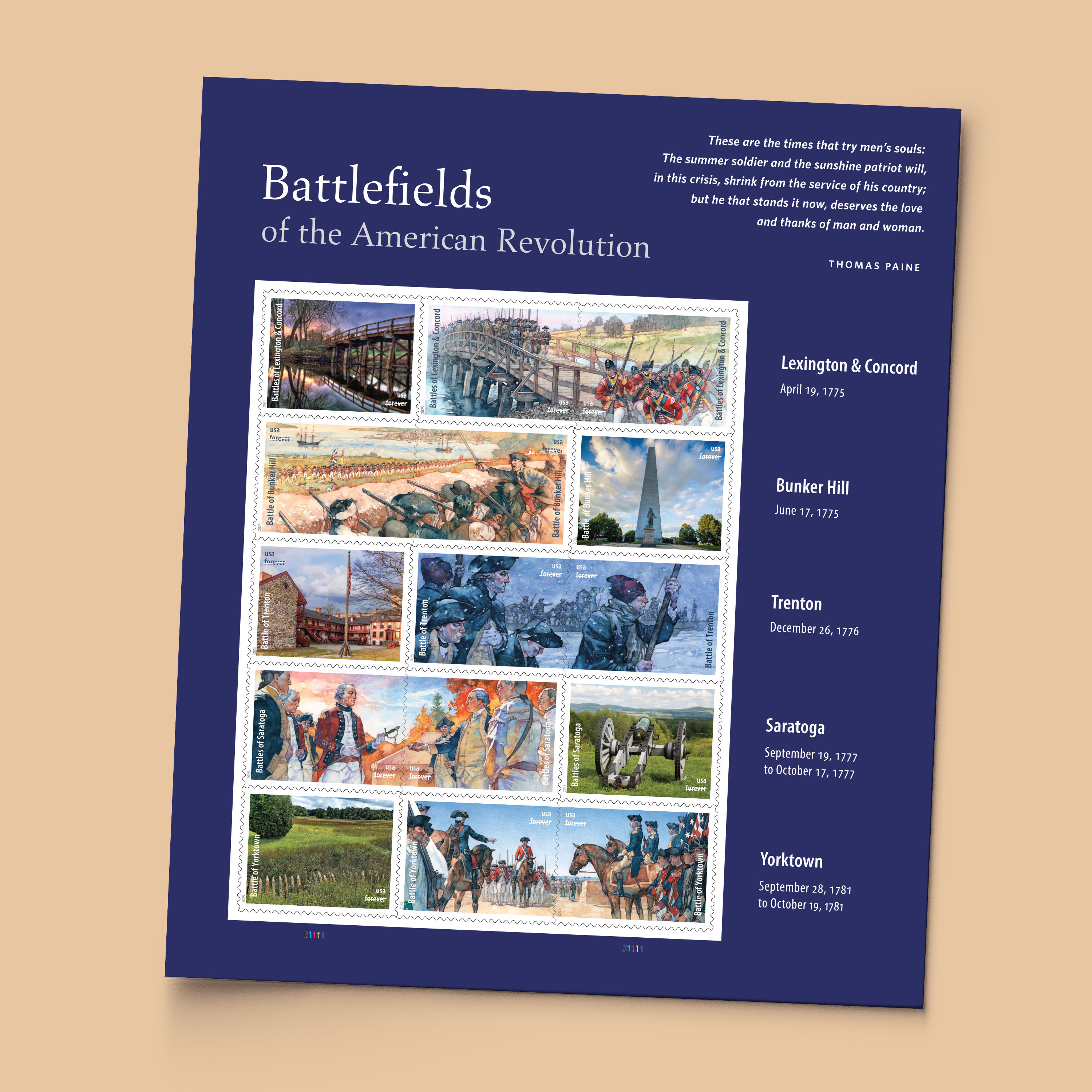

Eyewitness to Independence

“Looking back, it seems predestined,” muses artist Greg Harlin as he ponders his role as the illustrator for the Battlefields of the American Revolution stamps. “I was born on the Fourth of July in Washington, D.C., into a home decorated in colonial style. I drew a lot of minutemen when I was young, copying the art in our home.”

Many years later, a commission from a Revolutionary War site in Vermont reminded him of those childhood drawings and brought new focus to his work. “I’d been illustrating history for most of my career,” he recalls, “but there was something special about these pictures that felt like home.”

Sharp-eyed stamp buyers may recognize Harlin’s style. He recently created art for issuances that focus on colonial America or the early history of the United States: two War of 1812 issuances in 2014 and 2015, Repeal of the Stamp Act in 2016, and Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor in 2020.

If his work makes you feel like you’re immersed in an engaging story, it’s little wonder: Harlin often acknowledges the influence of Howard Pyle (1853–1911), whose definitive illustrations for countless books earned him acclaim as the “father of American illustration” — and a spot on the 2001 American Illustrators stamp pane.

“I hope to share how it felt to be there when history was happening.”

“Pyle taught me the need to live in your picture: ‘feel its mood and action in every part of you,’” Harlin explains, citing the words of the renowned art teacher almost as if he had studied with him more than a century ago. “I hope to share how it felt to be there when history was happening.”

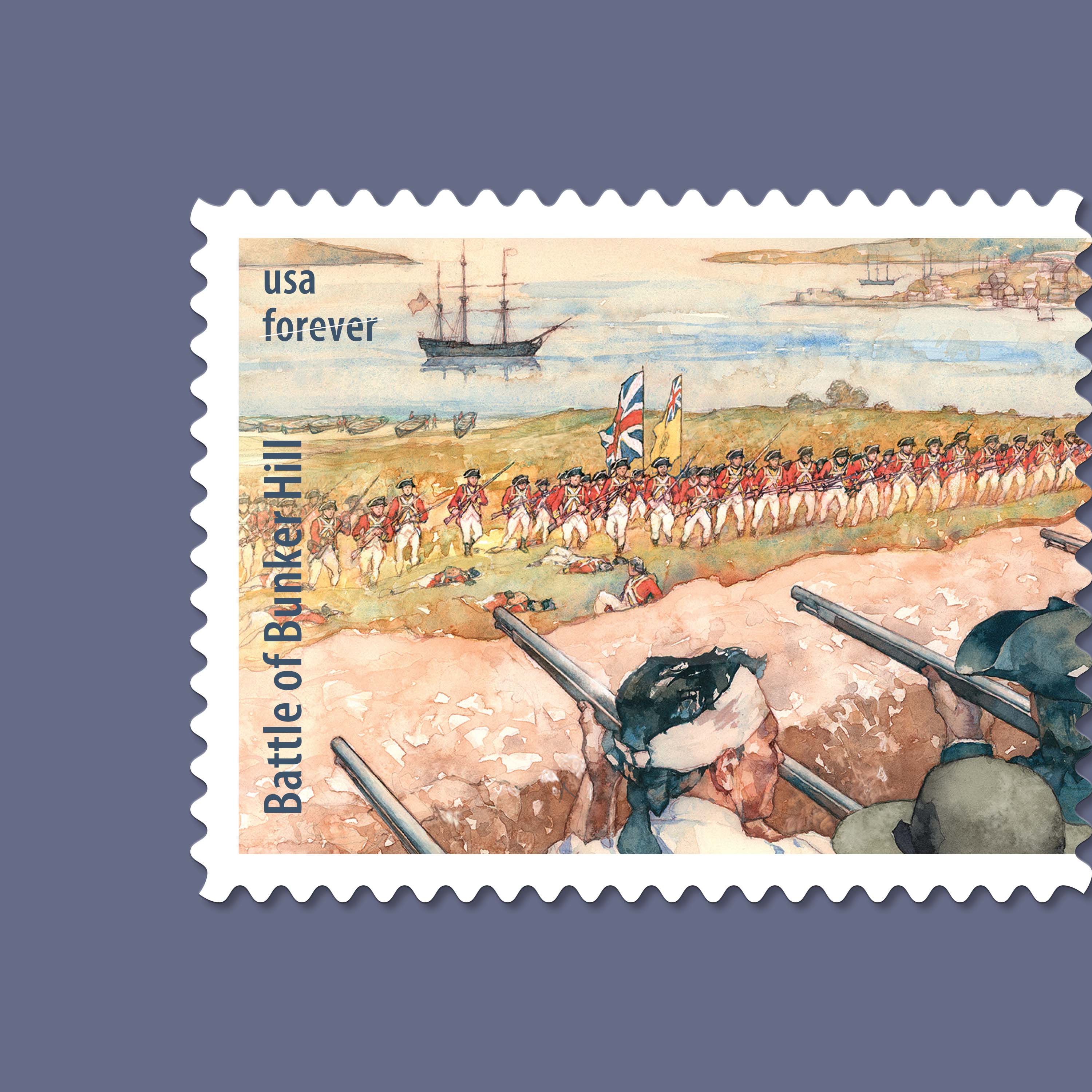

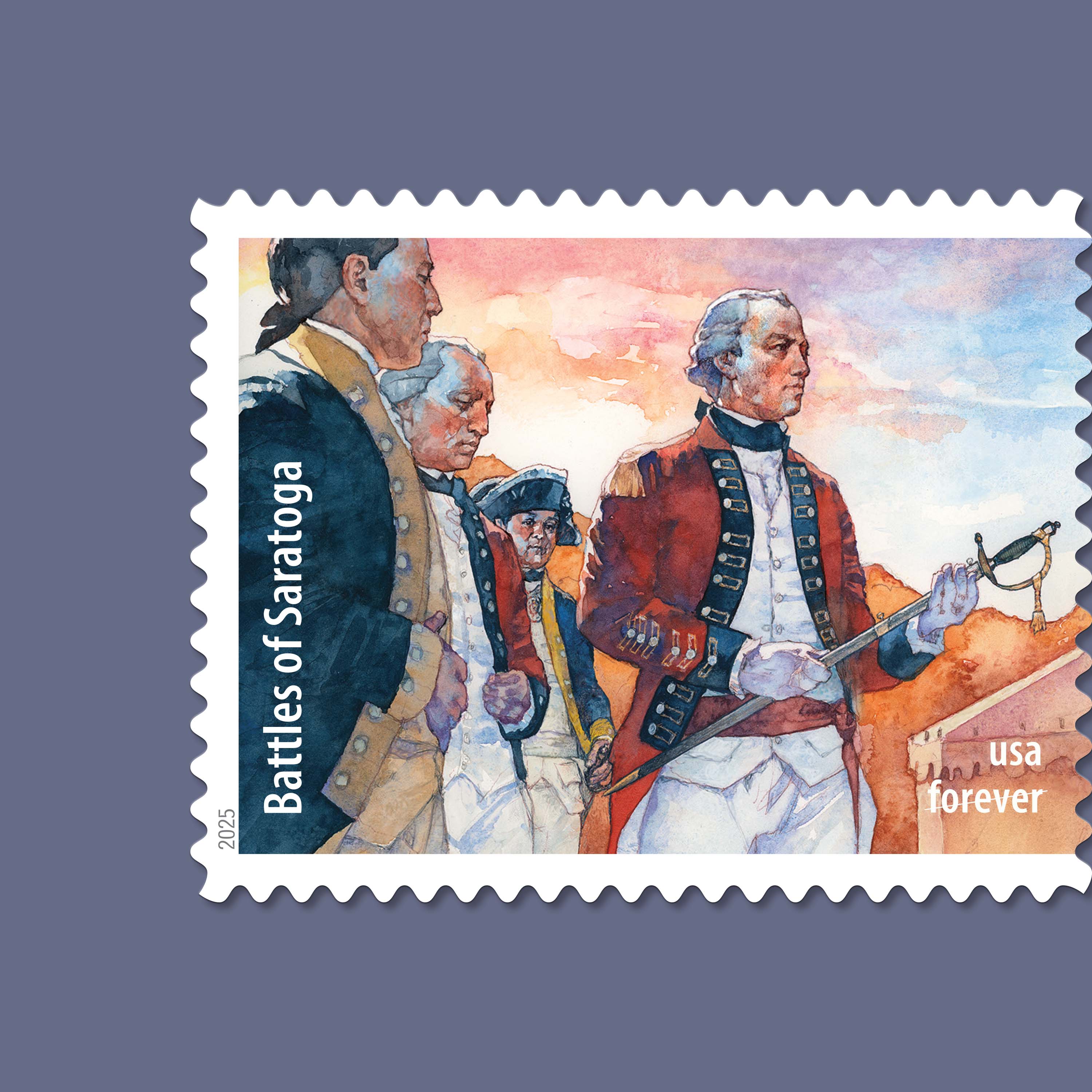

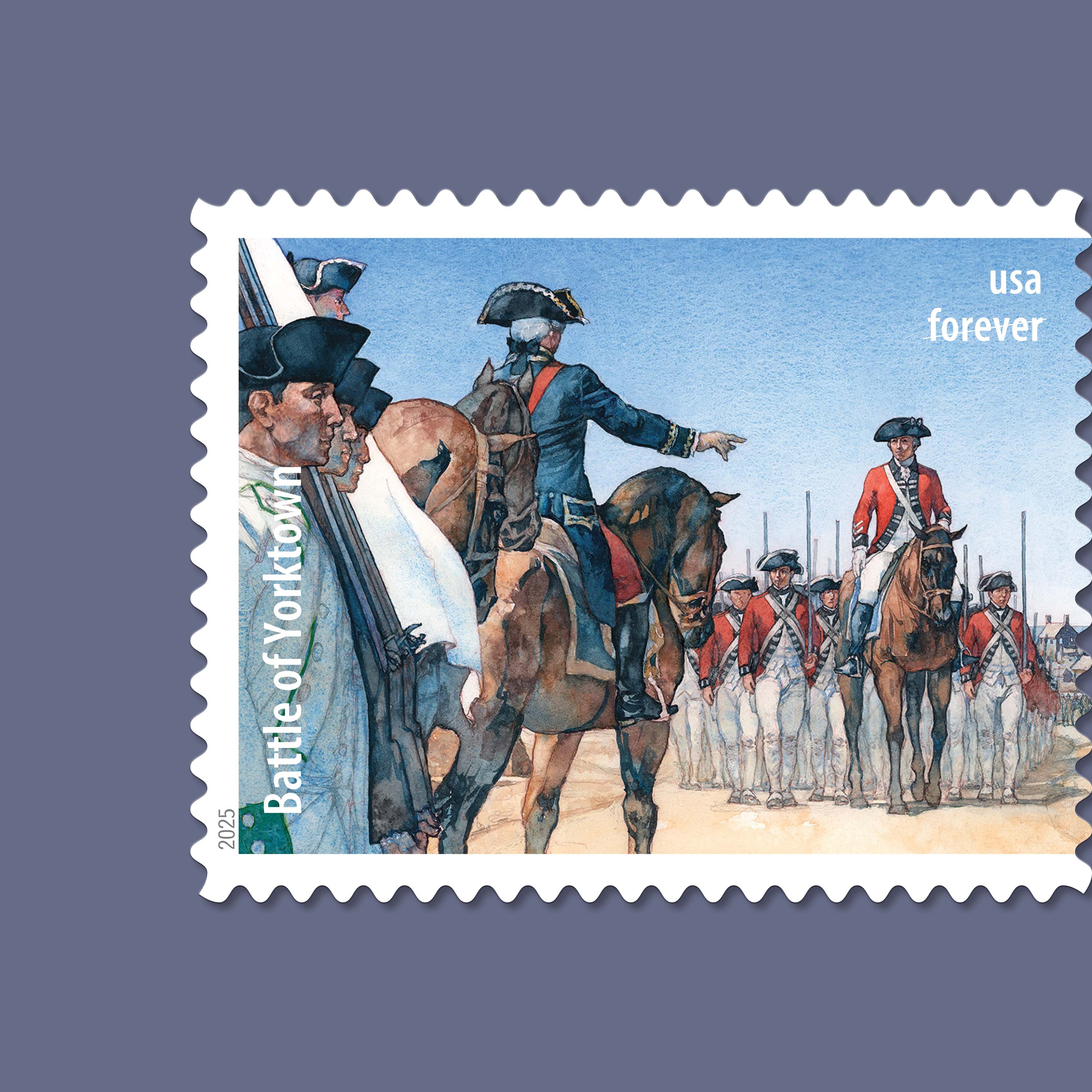

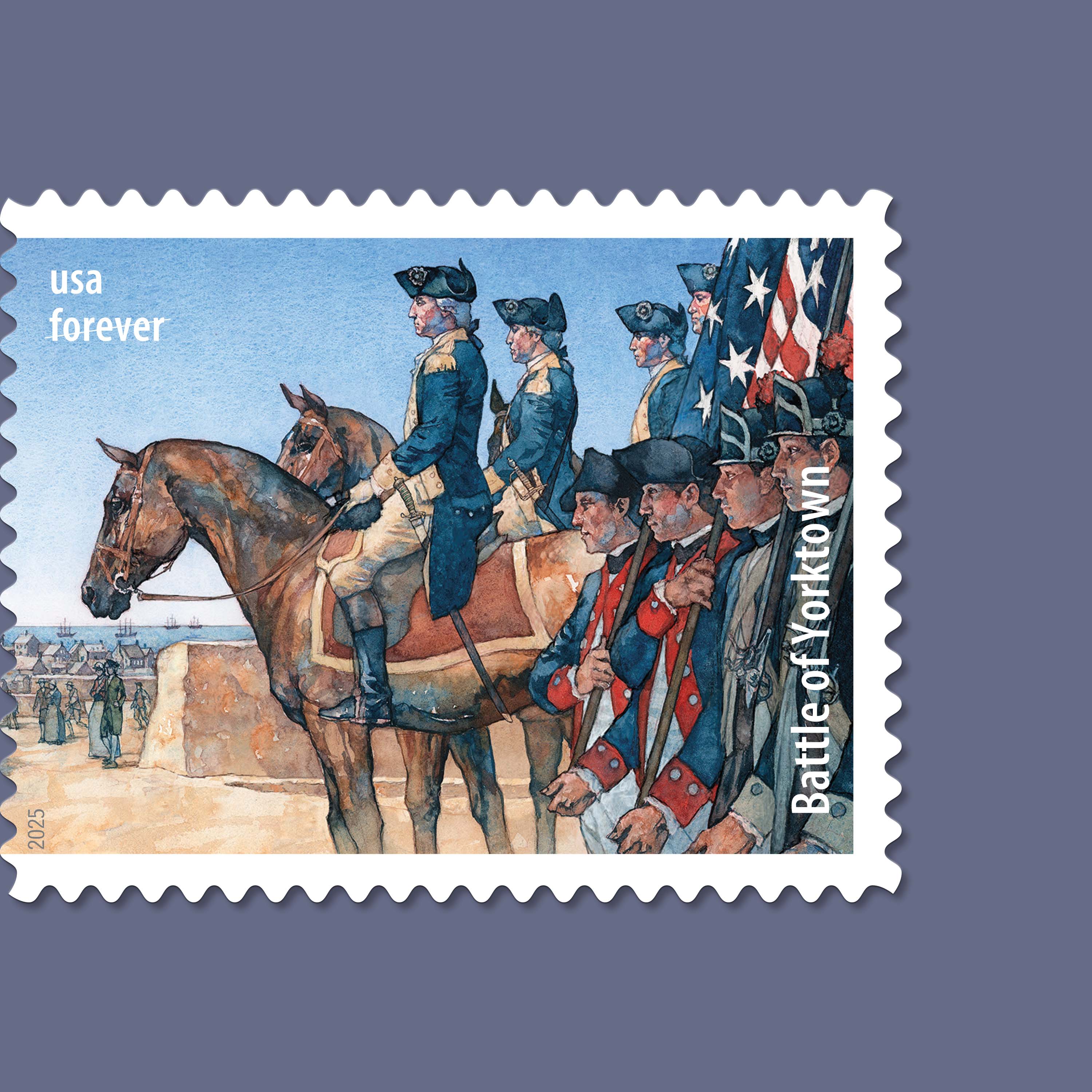

When they brainstormed their approach for these stamps, Harlin and art director Derry Noyes agreed on the importance of varying the illustrations by showing scenes from the battles as well as peaceful moments, without depictions of explicit violence. “I can hint at it indirectly,” Harlin observes, “but its terrible truth is most vivid when someone fills it in themselves in their own imagination.”

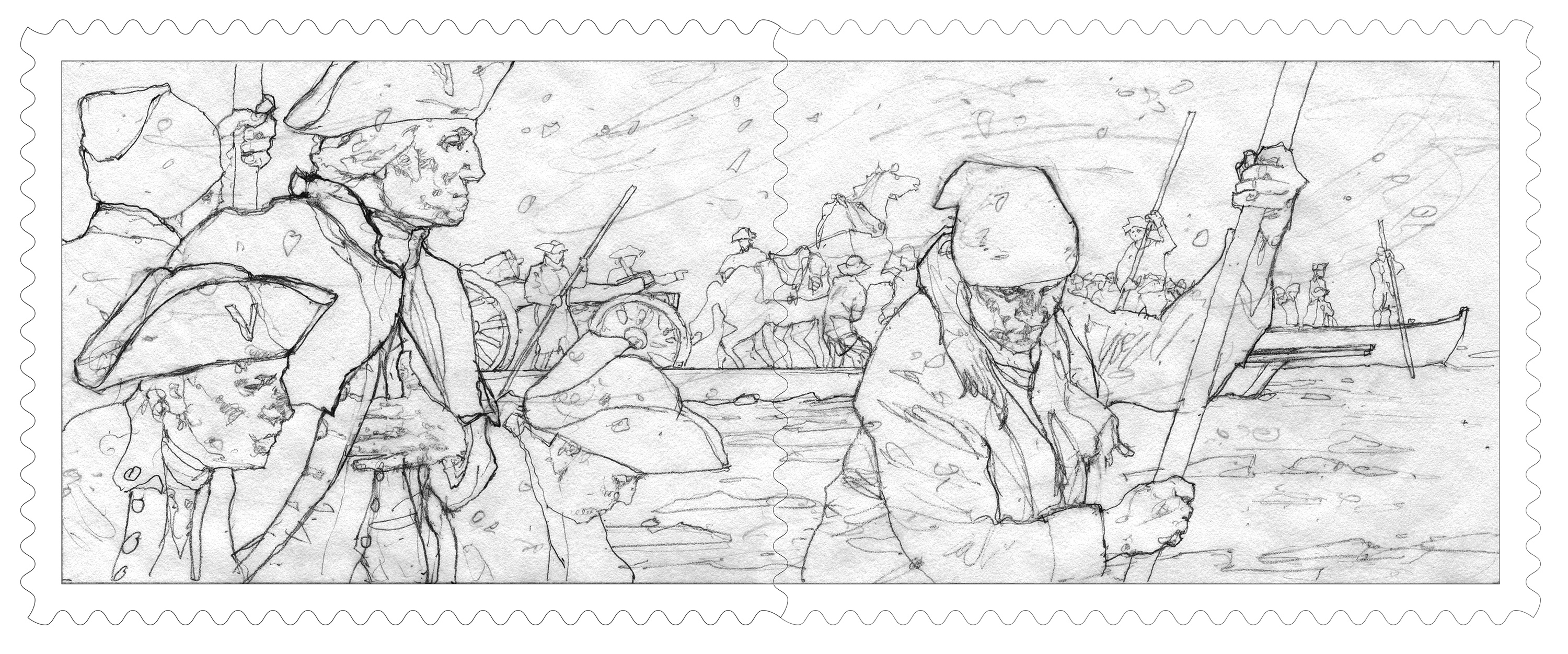

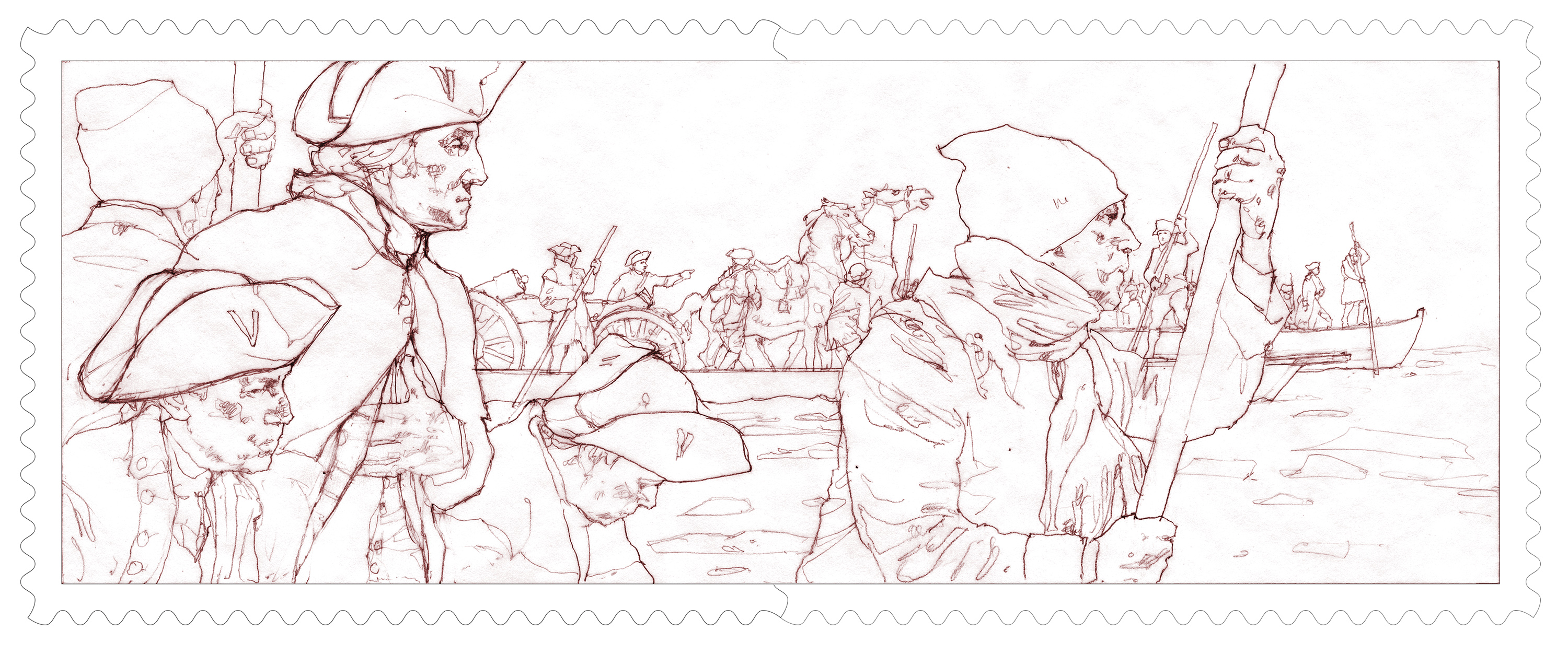

Varying the subject matter beyond the height of combat also presents an opportunity for the public to refresh their knowledge of the American Revolution. One historian who reviewed the stamp art was excited to see George Washington crossing the Delaware, commenting that many Americans may not remember why the commander in chief and his army crossed the river on a cold, snowy Christmas night, or where they intended to go.

Emphasizing the crossing as the prelude to the 1776 Battle of Trenton — where a much-needed victory saved the revolutionary cause — Harlin’s illustration also pays tribute to crucial support personnel: the many skilled boatmen from Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania who made the crossing possible.

The level of detail in Harlin’s illustrations — right down to the shapes of hats and the buttons on a general’s coat — is possible only because he first commits to understanding the broad outlines of his subject. “I usually start the research process in my personal library,” he says. “I have so many excellent books I’ve accumulated over the years, and I always add more with each new project.”

He also reads eyewitness accounts of the events he depicts, and he keeps up with the latest scholarship to help him interpret centuries-old sources. “In the beginning, I’m getting a sense of the big picture significance of the event,” he says. “Towards the end, we’re researching details of uniforms or landscapes.”

Asked about the significance of his work in light of the upcoming “USA 250” celebrations, Harlin grows thoughtful, viewing the next few years of ceremonies and commemorations through the long lens of history.

“One thing I’m feeling is how young our country is,” he says. “I’ve been here for a quarter of its existence! So maybe it’s not surprising that we’re still working our way through those not-so-long-ago turbulences. I’m hoping that the anniversary remembrances help re-focus us and reunite us around the ideals of our founding.”