How It Was Made: The 2026 Lunar New Year • Year of the Horse Stamp

How a three-dimensional mask and a master photographer keep a beloved stamp series galloping forward

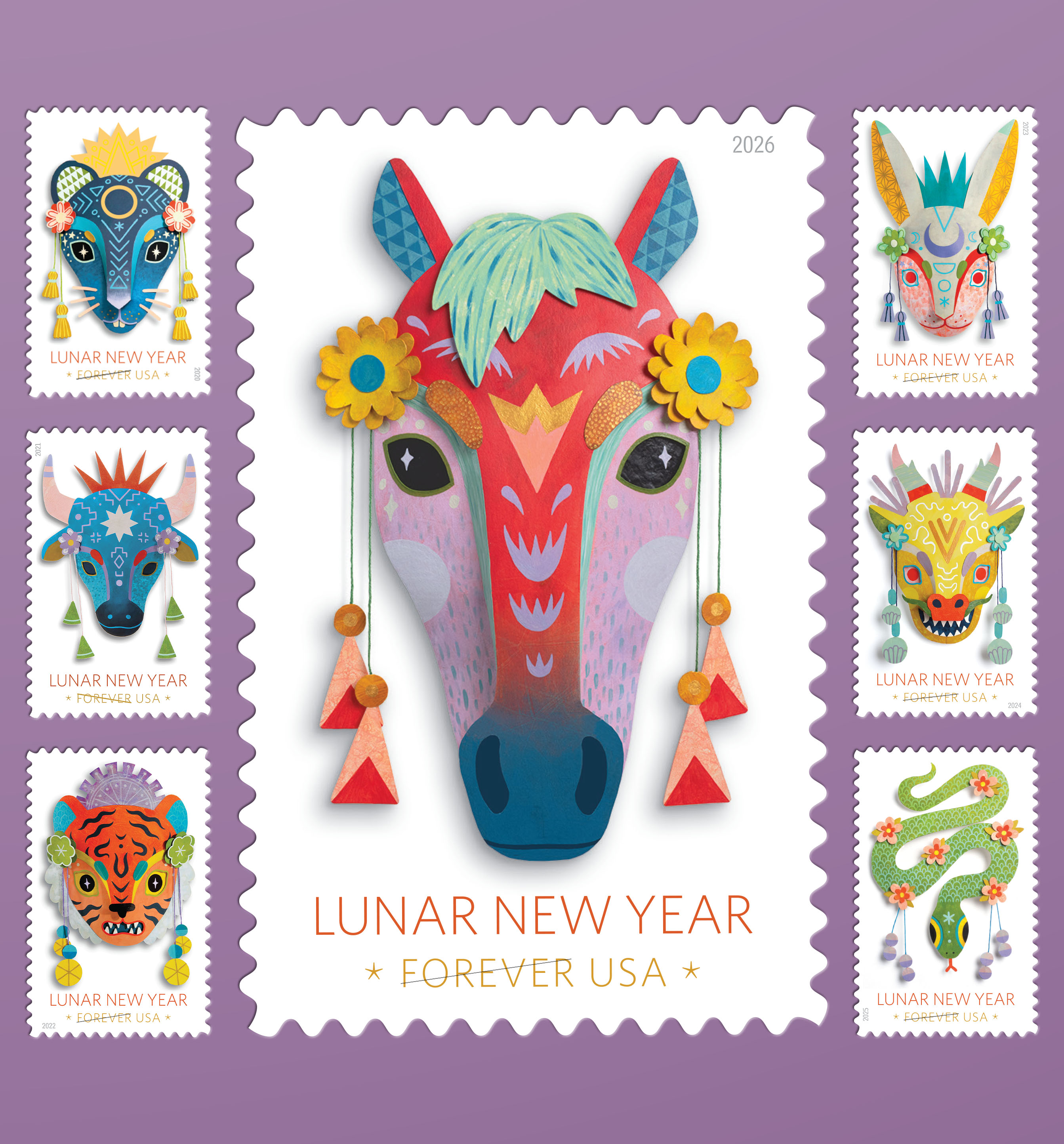

For more than three decades, the United States Postal Service’s Lunar New Year stamp series has delighted collectors with its vibrant images. Two previous award-winning Lunar New Year series ran from 1992 to 2004 and from 2008 to 2019, and showcased the art of Clarence Lee and Kam Mak, respectively. The first featured images of the 12 zodiac animals using traditional Chinese paper-cutting techniques to create the artwork, while the second series featured colorful painted images depicting some common Lunar New Year holiday traditions.

In the current Lunar New Year series, masks take center stage, each one a handcrafted interpretation of the year’s zodiac animal designed by artist Camille Chew under the creative direction of art director Antonio Alcalá. With the 2026 Year of the Horse stamp, the series continues its bold exploration of color, texture, and symbolism, offering a striking fusion of contemporary design and traditional imagery.

But behind each artwork is an equally intricate process, one that requires meticulous coordination between artist, art director, and photographer. For the Year of the Horse release, veteran photographer Sally Andersen-Bruce once again stepped behind the camera to transform Chew’s paper-cut horse mask into a definitive, print-ready image.

A Mask with Movement — and Challenges

“I was thrilled and honored when I was asked to photograph Camille’s Lunar New Year horse mask, which would appear on a United States postage stamp,” Andersen-Bruce says. “What fun!”

The enthusiasm is understandable: Chew’s masks are intricate, dimensional works with layers of color, carved shapes, and hanging decorative elements that bring each animal’s personality to life. But those same elements create difficulties when translating a sculptural object into a two-dimensional printed form.

“The mask is three dimensional and the decorative pieces dangling on either side of the mask can pivot,” Andersen-Bruce explains. “They are not parallel to the lens, and the threads that hold the pieces can be moved to different lengths. Adjusting the length of the threads and securing the floating pieces so they are parallel to the lens is a challenge.”

Add to this the fact that every stamp in the series shares the same general dimensions, but the masks Chew creates vary year to year in shape and scale. “I try to fill as much of the ‘stamp area’ with the mask and not negative space,” the photographer says. “However, I always keep in mind that the art director will be adding the typography later, so I allow enough negative space for the type.”

The result is a puzzle: maximize the presence of the mask while preserving functional clarity for the design. The images must feel consistent across years — an unbroken visual lineage — while still reflecting the unique character of each zodiac animal.

Studying the Mask Before It Meets the Camera

Before lights are positioned or backdrops chosen, the photographer spends time simply observing: “Once I receive the mask, I quickly hang it on the wall and look at it for as long as I need to learn the challenges it may present,” Andersen-Bruce says. “It’s not the final position for the photo — just for me to become familiar with the mask and its unique characteristics.”

This quiet, contemplative phase allows her to note how its structure catches light, where shadows may fall, and how its various layers interact visually. On the Year of the Horse mask, the depth between layers was minimal — something that strongly influenced her lighting strategy.

“This particular mask had many layers, but the depth between them was minimal,” the photographer explains. “I had to create lighting that would define the layers clearly. The shadows would create the separation between layers, which is more difficult to do when there is a small distance between them.”

For viewers, those subtle adjustments are invisible — but essential. Without careful sculpting through light, the mask could appear flat or confusing when reproduced at stamp scale. Years of experience photographing the earlier masks informed Andersen-Bruce’s approach, helping her maintain continuity across the series. “Matching the lighting to previous Lunar New Year masks is a skill learned from years of observing light and shadows on many subjects,” she says.

A Close Collaboration with Art Director Antonio Alcalá

Once the initial lighting is set and the mask has been placed on the photo set, the next element of the process begins: collaboration with the art director.

“Working with Antonio is an absolute pleasure,” the photographer says. “He is very clear in describing exactly what he wants the final image to look like.”

She begins by sending a series of initial images to Alcalá. From there, the two begin an intense, highly detailed dialogue.

“Antonio responds with changes in lighting, repositioning of free-floating objects, and adjustments to the density of the shadow. I just have to do exactly what he describes,” Andersen-Bruce says. “It is seldom that I achieve this on the first go-round, but I listen very carefully and do my best to achieve those refinements and changes.”

Alcalá may ask her for input, but within clear parameters. “I’m aware that it has to match the other masks in the series,” she adds. “At this point in the process, the two of us work closely together. He is the creative director, and he has created this entire series of stamps. And Camille has completed her task, which was creating the mask to meet Antonio’s specifications.”

This trio — artist, photographer, and art director — forms the backbone of the entire series, each person stepping in at a precise stage. Chew gives material form to the zodiac animal; the photographer brings that form into the realm of light and shadow; and Alcalá synthesizes it all into a finished design.

A Series That Has Captured Public Imagination

Now more than halfway through the run of the current Lunar New Year series, Andersen-Bruce has developed a deep appreciation for the breadth and personality of the collection.

“I think this collection is fun and fabulous,” she says. “The general public seems to love it. It’s very different from the two earlier Lunar New Year stamp series.”

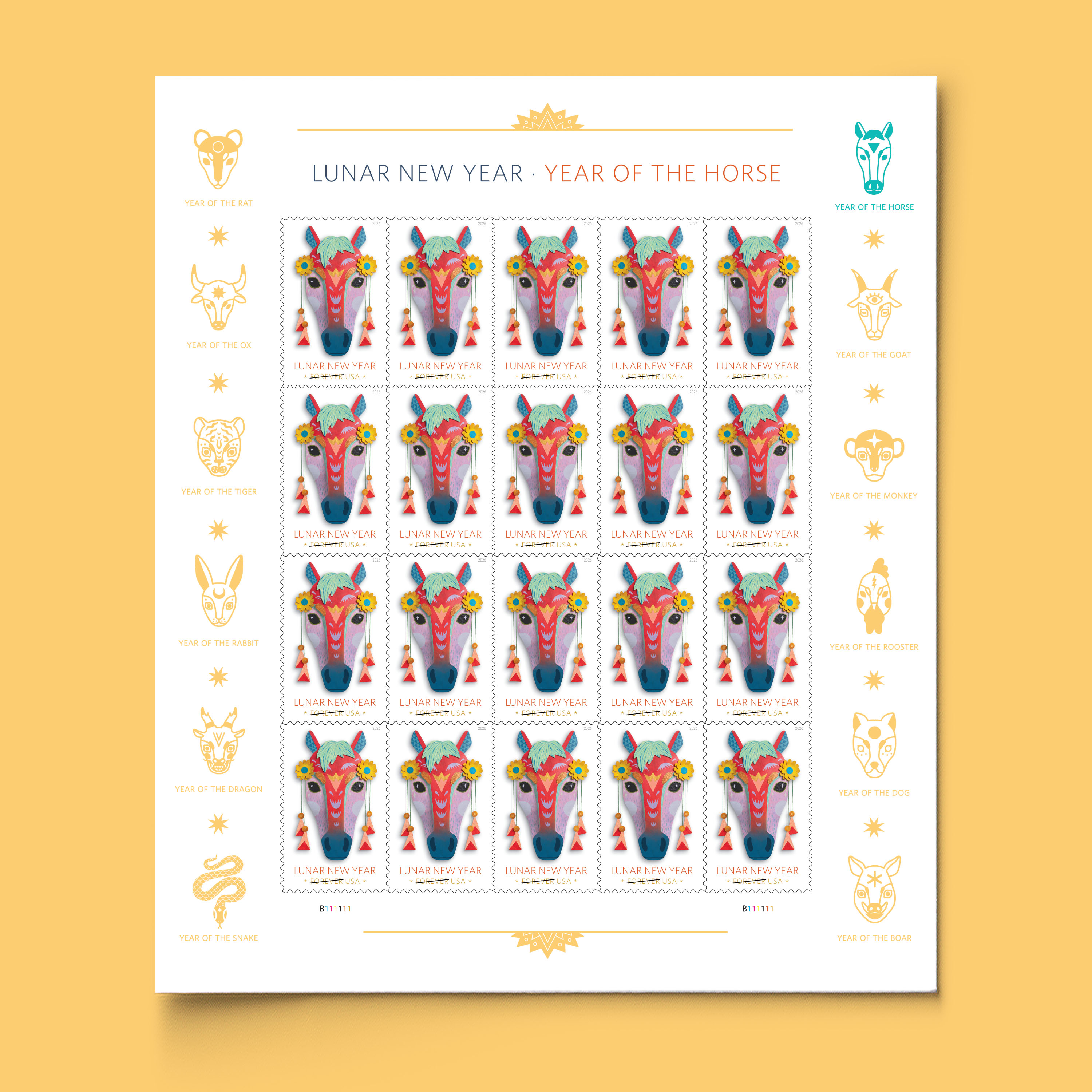

Much of the appeal lies in the masks’ expressiveness and the interplay of traditional motifs with modern aesthetics. Each stamp feels festive yet contemporary, detailed yet immediately readable, even at the tiny scale of a postage stamp. Embellishments like glittering foil and a colorful selvage — the outer area of the stamp pane — featuring the 12 zodiac animals, make each Lunar New Year pane stand out on the shelf, and on letters and packages.

Still, despite Andersen-Bruce’s accumulating experience with the series, every new design brings fresh surprises. “Each mask has its own challenges,” she says. “I never know what it will be until I actually see the finished mask. I go into a photo shoot expecting the unexpected. It’s different every time.”

A Galloping New Addition

The 2026 Year of the Horse stamp promises to extend the series’ distinctive visual language while bringing new energy to the lineup. The horse — a symbol of vitality, ambition, and forward momentum — arrives rendered in Chew’s signature style and is shaped further through careful lighting and direction. It is the product of craftsmanship at multiple levels: artistic, photographic, and editorial.

And though it may measure barely an inch once printed, the work behind it is anything but small. Each stamp represents hours of observation, adjustment, collaboration, and refinement. The result is not only a piece of postage, but a miniature work of art.