Peace, Liberty, and Safety

Dedicated in Philadelphia, the First Continental Congress, 1774 Forever® stamp commemorates one of the most significant turning points in the lead-up to the American Revolution — and helps kick off the Postal Service’s exciting celebration of the nation’s 250th anniversary.

Convened in Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774, the First Continental Congress was made up of 56 delegates from every colony except Georgia, among them future presidents George Washington and John Adams.

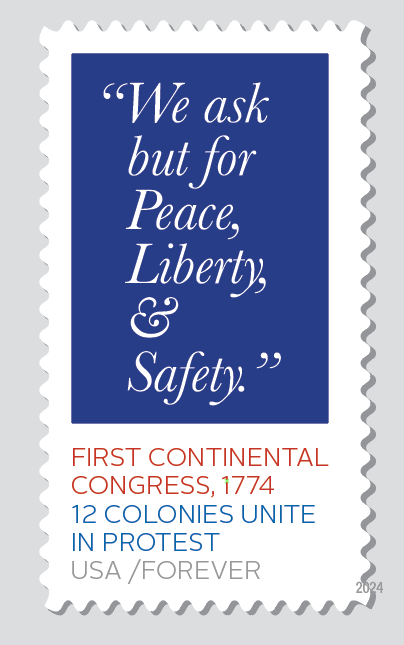

The stamp design highlights a brief but powerful plea taken from a petition sent by the Congress to King George III in October 1774 — “We ask but for Peace, Liberty and Safety.”

The colonies unite in protest

In the months leading up to the October 1774 petition, relations between Britain and the American colonies had drastically and rapidly deteriorated. Britain had closed Boston Harbor following the Boston Tea Party the previous December and replaced the elected council of Massachusetts with one appointed by the king.

Money, food and other much needed supplies flooded into Boston from the other colonies. At the same time, a new sense of unity took hold. If Parliament could take this kind of action against Massachusetts, the colonists reasoned, then others might be next.

After several weeks of debate, the First Continental Congress proclaimed every American colonist was “entitled to life, liberty and property.” The Congress than issued one of the most important documents of the era: the Articles of Association, which unified the colonies in a trade boycott and, importantly, lay the foundation for government during the Revolution.

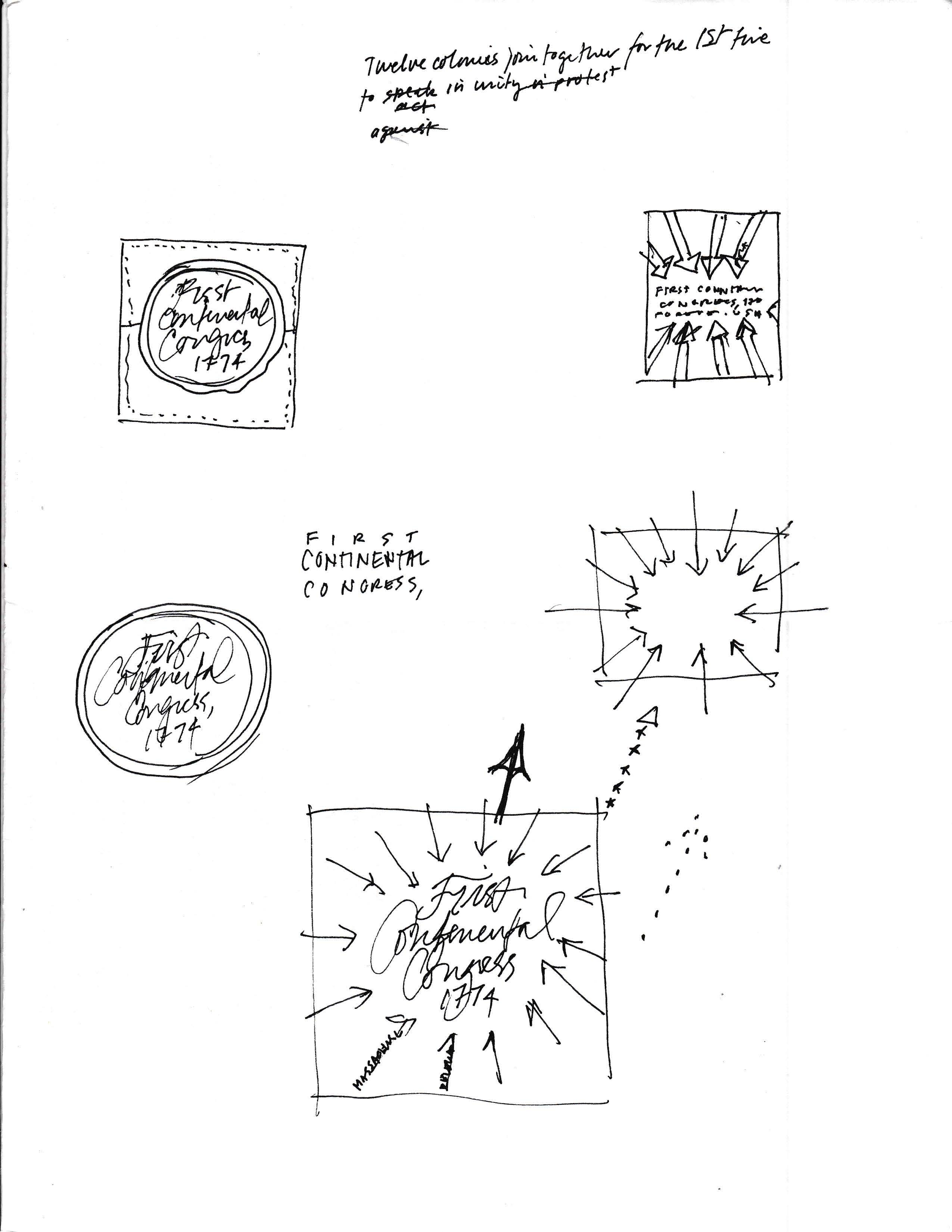

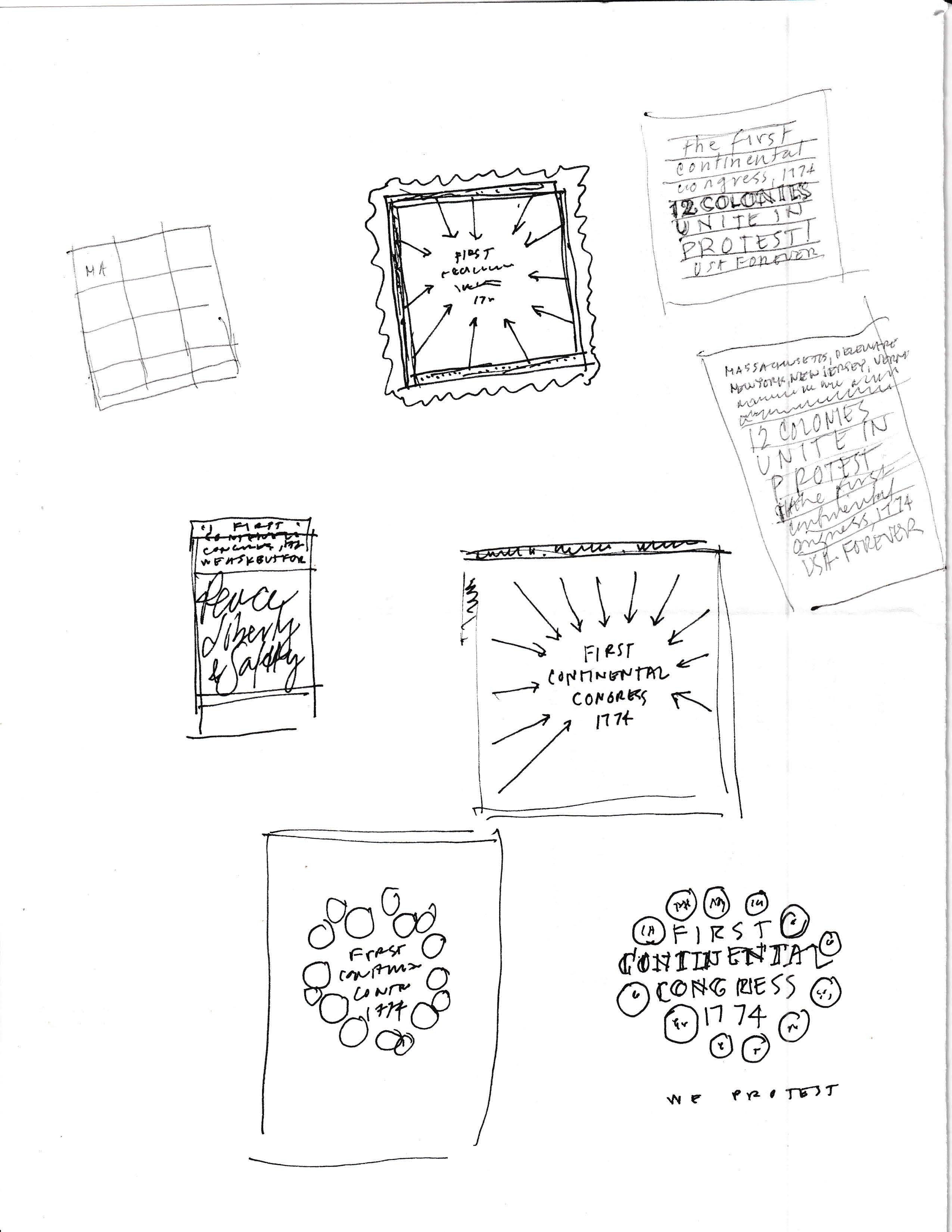

Searching for a design

Commemorating such a crucial moment in U.S. history on a stamp presented several challenges for art director and stamp designer Antonio Alcalá.

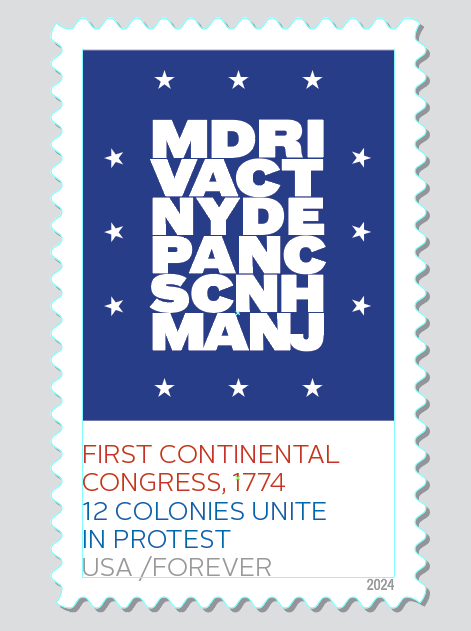

“The art had to make clear what the accomplishments of the Congress were,” he explains, “and that there were only 12 colonies present.” He also wanted the stamp to convey that this was not the Declaration of Independence but an organized attempt to protest what the colonists viewed as increasing threats to their freedom imposed by the British government.

“My first sketches were searching for a way to effectively represent the idea of 12 colonies joining for the first time to act in unity,” he says. “They show arrows coming together or a grouping of colonies, but none of these directions felt very promising to me.”

Alcalá then tried another approach: abbreviating the name of each colony in block letters and rendering them all tightly against one another to “suggest the colonies rushing together to form a solid unit.”

“The problem with this approach” he reflects, “is it looked interesting, but was too difficult to decipher — at least in this context.” He also produced a version using calligraphic type that seemed promising. Calligrapher Yukimi Annand created numerous variations of this composition but, says Alcalá, “a solution was never found using calligraphy to represent the colonies coming together.”

At this point, Alcalá began looking for a way to incorporate the key phrase from the October 1774 petition to the king into the stamp design. Although notions of complete independence from Britain were not yet widespread, the phrase reflects the newfound sense of unity that had taken hold in the colonies.

“It is the most forceful, independent-sounding part of their missive to the British monarchy, and it remains a strong idea today,” says Alcalá, who took a layout with the abbreviations and replaced them with the phrase.

“From there,” he says, “it was a hop, skip, and jump to the final design.”

First steps toward independence

Presented in London by Benjamin Franklin, the October 1774 petition and its plea for peace, liberty, and safety was rejected by the king, who mistakenly believed that the American colonies would never unite in opposition to British rule.

Convened on May 10, 1775, the Second Continental Congress served as the provisional central government until 1781. In addition to authoring the Declaration of Independence in 1776 as well as the 1777 Articles of Confederation, the Congress issued money, created a postal system, and ultimately named the United States of America.